ASEAN MEKONG INTEGRATION

The “Association of South-East Asian Nations” or “ASEAN” was formed from the ASEAN Declaration in Bangkok on 8th August 1967 (as a successor to the Association of South-East Asia, “ASA” in 1961), and is just four years younger than the EEC (now the EU). ASEAN is now a grouping of ten geographically, culturally and politically diverse countries, although initially consisted only of those countries which avoided any socialist experimentation: Singapore/Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines and Indonesia. Most of the Mekong countries joined later: Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos.

ASEAN has 651 million people and a land mass of 4.5 million sq kms (50% larger than India and one-half the size of China), and a nominal GDP of US$ 3 trillion (on a PPP basis 4x higher at $13 trillion) and US$ 4,600 nominal GDP per capita. By comparison, the EU has twenty-eight countries, 513 million people, and an almost identical land area of 4.48 million sq kms, but it has a nominal GDP that is 7X higher than ASEAN at US$ 19 trillion (or $23 trillion translating to just 2X on a PPP basis), and a US$ 37,300 nominal GDP per capita. The likelihood is that ASEAN will narrow the gap between its nominal and PPP GDP over the next few years, generating substantial gains for investors.

What is common to all ASEAN countries is the agricultural economic base (except for Singapore & Brunei) and their consequently more manageable workforces, their Chinese (mostly Fujian) diaspora business culture, and their Japanese/Taiwanese/Korean led industrial investment. The Mekong countries share a common Buddhist heritage, but are a mixture quasi-democratic, and factional 1-Party States.

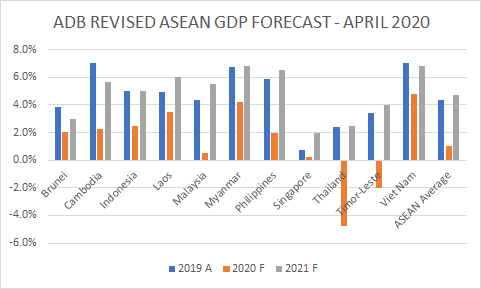

The oldest cultures in ASEAN, the Mekong countries are the least developed, due to their proximity to China and its socialist sphere of influence from 1950-1980. That proximity is now a positive as China embarks on its “Belt & Road” initiative and its manufacturers rush to avoid rising labour costs and US/China trade friction, diversifying production to Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Myanmar. Currently the former closed countries, Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos, “continental ASEAN” or the old Indochina, are now leading ASEAN in growth from their lower economic bases, and after a temporary lapse in 2020, are all expected to be back to 6-7% growth rates in 2021.

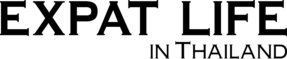

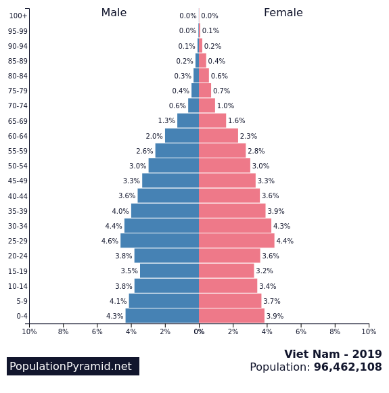

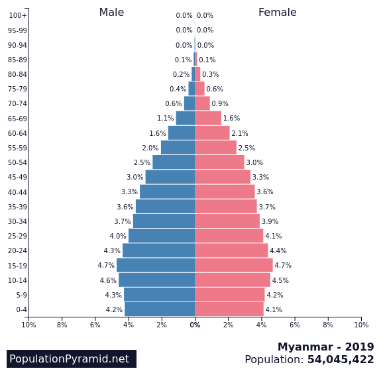

Demographics is a key determinant of economic activity, with Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia with consumption rich median 35-45 year old population pyramids; Philippines and Vietnam progressing 25-35 year median; Myanmar, Laos & Cambodia 15-25 years, still too young to consume but sources of abundant labour. As the general populace becomes more demanding, all political leaders must turn to somewhat populist policies. This will ensure many decades of growth ahead.

Mekong countries are generally emulating the successful Thai economic model, beginning with agriculture & food processing, then moving on to increased tourism, export driven manufacturing, and finally domestic consumption. Thailand has the advantage of having 20 years head start, but is already facing stiff but healthy competition from Vietnam in the agribusiness and manufacturing sectors. To some extent, there is room for all these countries to succeed, as they have India and China as neighbours. Thailand, with its excellent infrastructure & human resources, has a good chance to maintain its lead in the service sector, as a hub for tourism, entertainment, retail & healthcare, together with having numerous international schools and services for regional headquarters.

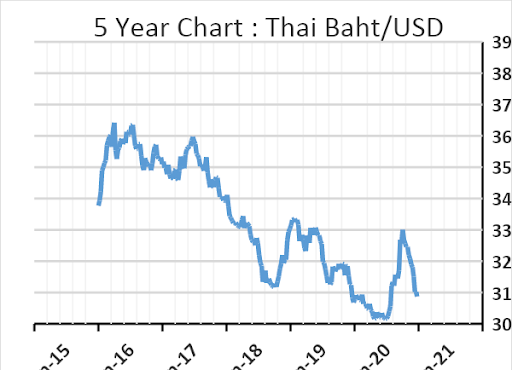

However, given Thailand’s legacy exchange controls, Singapore & Hong Kong will likely retain the crown for financial services & banking for the Region. Due to their large foreign exchange reserves and surpluses, the Thai Baht and Singapore Dollar will likely remain strong as haven currencies. Also, Chinese initiatives like RCEP, Belt & Road, and the Asian Infrastructure Bank will encourage more transactions to be done in regional currencies. US Dollar dependence may gradually wane.

The extraordinary global political reaction to COVID has reinforced existing trends towards a tri-polar world: Asia dominated by China/Japan; Europe/Middle East/Africa; and North America (+South America). Given the extremely low incidence of COVID in South-East Asia in particular, governments will likely soon form sub-bubbles, starting with the Mekong Region “bubble” (CLMV in Thai speak). Thailand ranks 94th in the COVID table, Myanmar 182nd. Laos 187th, Vietnam 188th, and Cambodia 189th. Border trade (already 20% of Thailand’s total trade), and intra-regional services will enjoy a quick resurgence.

|

Intra-ASEAN Trade 2018 (% of Total) |

|||

|

|

Exports |

Imports |

Total Trade |

|

Brunei Darussalam |

31% |

33% |

32% |

|

Cambodia |

6% |

56% |

33% |

|

Indonesia |

23% |

27% |

25% |

|

Lao PDR |

47% |

68% |

58% |

|

Malaysia |

27% |

29% |

28% |

|

Myanmar |

31% |

38% |

35% |

|

Philippines |

16% |

22% |

20% |

|

Singapore |

29% |

22% |

26% |

|

Thailand |

26% |

22% |

24% |

|

Viet Nam |

8% |

15% |

11% |

|

ASEAN |

22% |

24% |

23% |

|

Source: oec.world |

|

|

|

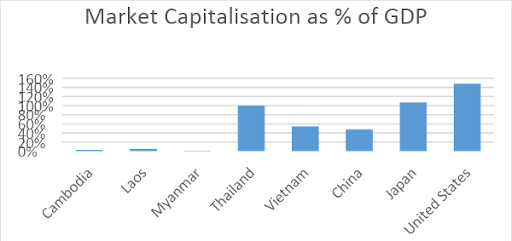

The core ASEAN countries have long established stock markets, with Indonesia’s founded in 1912, Philippines 1927, Thailand in 1962, Malaysia 1964, and Singapore opening in 1973. As with the new Mekong markets today, these markets started slowly and it took many decades for them to reach a true representation of their underlying national economies. Many of the richest business families preferred to keep a low profile and investment in the capital markets were left to their second or third generation scions, who are now officially in charge. The same pattern may follow in Vietnam, Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos. Although we expect Myanmar to enjoy an accelerated progression due to its private sector need for capital, provided the appropriate incentives can be put in place.

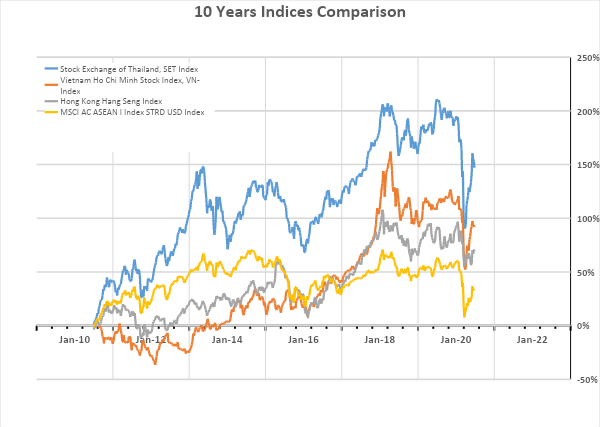

A question I’m often asked, is “Why do ASEAN stock markets tend to underperform their underlying economies”. For instance in the last 10 years from 2010-2020, ASEAN economies have averaged over +5% per annum GDP growth, but their stock markets increased just +3% per annum, with the Morgan Stanley total return MLSO Index gaining +33% in ten years. Over the same period Hong Kong’s HSI gained +71%. However the Mekong Indices have done much better, with Thailand’s SET Index +151% and Vietnam’s VNI Index +91%, so it is not true that all parts of ASEAN are perennial under-performers. Infact ASEAN Index performance has mainly been dragged down by Indonesia & Malaysia currencies. Meanwhile, healthy surpluses have kept the Thai Baht and Singapore Dollar strong, with The Cambodia Riel, Laos Kip, and Vietnamese Dong essentially pegged to the US$.

Total Return of ASEAN & MSCI Indices : 2010-2020 |

||

|

|

Currency |

Total Return (%) |

|

SET Index |

USD |

151.4% |

|

VNIDEX Index |

USD |

91.2% |

|

HSI Index |

USD |

71.5% |

|

MXASJ Index |

USD |

80.2% |

|

MISO Index |

USD |

33.3% |

|

Source: Bloomberg – 24 June 2020 |

|

|

We should differentiate between corporate earnings growth and share price performance. Listed company earnings have grown +9% per annum for the last 10 years, easily outpacing the underlying 5% GDP growth. The fact that equity indices have only gained +33% in the same period, is an indication of valuation fluctuation on the back of global capital flows, local liquidity, impact of foreign exchange rates on these export driven economies and investor sentiment. Corporate earnings may themselves swing widely depending on the corporate discipline, leakage and accounting within particular companies.

The cyclicality of ASEAN in the past has meant that returns would be massively skewed by the timing of entry. The 1996-98 Asian Crisis and the 2008 global financial crisis amounted to major value resets, and the 2020 COVID shut-down created a fantastic buying opportunity in the midst of a financial panic and temporary economic dislocation. In South-East Asia we do not expect the economic turbulence to be protracted, since government balance sheets are much stronger than ever before. Average government debt to GDP in ASEAN is less than 60% versus 100% in the UK and 108% in the US. In addition, foreign exchange reserves in ASEAN are over US$ 1 trillion or 1/3 of total regional GDP versus China at 3 trillion or 25% of GDP. Similarly, total ASEAN debt (combined government and private) stands at a manageable 101% of GDP versus 203% in Germany, 303% in China and 310% in the US.

In the face of all these factors, a buy & hold or index/basket investment approach doesn’t work as well as it does in more mature markets. ETFs are well established in Asia, but trading the swings has proved to be the best way to generate returns. The bargain levels of March 2020 may be gone, but the value opportunity and growth story remain intact.

A more active investment approach is required in ASEAN as in other parts of emerging Asia. The combination of diverse cultures, imperfect economic statistics, and varied levels of corporate integrity, means that qualitative as well as quantitative inputs need to be updated on a continuing basis from a mix of formal and informal sources. Understanding the cultures and politics of these countries, knowing who the players are and applying one’s own assumptions based on direct observation of the individual economies is vital. Contrarian timing must also be applied in order to benefit from the market cycles, and individual companies’ ever fluctuating popularities.

As institutions and regulators worldwide seek to progressively turn all investment professionals towards process rather than performance, they are in danger of being replaced by artificial intelligence (AI). ASEAN stands as one of the last bastions of common sense investing. Core ASEAN is not yet AI dominated, and not yet efficient in providing accurate information to all investors at the same time, so it likely has around ten or more years of alpha-active investing remaining, and the Mekong region at least 20 years or more.

Choosing managers in this environment should also be a qualitative process, not solely a quantitative process. Managers should be favoured who have a proven track record of managing volatility and stress analysis, and performance led rather than simply a bureaucratic “checklist” process. In more mature developed markets alpha generation tends to be confined to investment banking proprietary trading desks and hedge funds. Within ASEAN, retail investors still predominate as a counter-weight to the passive investment approach of the large institutions.

CONCLUSIONS:

- The Macro arguments for investing in the Mekong Region are clear: Shifting manufacturing from China; regional tourism; food demand & infrastructure linkage; and rising domestic consumption.

- Getting the right exposure is the hard part. Broad ASEAN ETF/Index Funds may not capture the growth. Country specific ETFs are more effective for those willing to trade the highs & lows, deciding the country allocation themselves reflecting their knowledge of the social, political and economic drivers of those countries.

- The logical way is to invest with independent and active managers’ offshore funds, avoiding process driven onshore index enhanced funds where flexibility tends to be lost and performance defeated.

- Experienced boutique managers with real experience are best placed to access the right opportunities in the Mekong Region. and

- Investors who take a medium to long-term view will be able to ride out the cycles, especially if they are contrarian and add to exposure on any major down-turn. Currently, markets are in middle ground, off their lows, but still good value compared to end 2019.

JEREMY KING is Trustee of the Knight Foundation