A glittering look at Bangkok global hotspot of bling. My time as a Gemologist-in-Training

Jewellery. What is it and why do we wear it? Across cultures and spanning the history of humanity, the act of adorning our body for women and men is both personal and universal. It can be art or seduction; it can be a form of protest, or of rebellion. Jewellery, what is says about us and its transformative effect, makes it much more than superficial.

I can link my interest in gemmology back to the boy king and his visit to New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was a long, long time ago when the Treasures of Tutankhamen exhibit rolled into town, but when it happened it was the hottest ticket in town. I was only a child dragged along for the outing by my enthusiastic Mother and her equally exuberant sisters’. Yet, even at that age, it was an electrifying experience. While the historic significance of the artefacts was lost on me, I was astonished by the crowds and the sheer number and array of objects – animal themed relics depicting lions, ostriches and falcons, myriad of gold and gem inlaid pieces some meant to be worn amulets, bracelets, collars and rings, others to embellish from ornate boxes to model boats to a coffin made entirely of gold. I’d never heard of lapis lazuli, quartz or turquoise before, nor did I grasp the rarity and craftsmanship of these discoveries. But I was hooked. Who created such amazing pieces? And why? The sensational discovery of Tutankhamen, a short-lived Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, revealed nearly 5,400 fabulous treasures so many it took ten years to document them all. The treasures in the tomb were found literally stacked in cases and boxes – necklaces, pectorals, amulets, pendants, bracelets, earrings, and rings of such superb quality they could rival any of our modern techniques.

But the ancient Egyptians weren’t alone in adorning themselves. Evidence shows even prehistoric humans decorated the body with shells, fish teeth and coloured pebbles. Over the years, jewellery forms continued to grow and expand to include ornamentation for every part of the body: Crowns, tiaras and combs for the top of the head; earrings and nose rings for the face; necklaces, brooches, breastplates and belts for the neck and torso and on and on. Jewellery in Ancient Rome was used to such an extent that gold rings were worn by noblemen, eventually jewellery became so democratised it spread even among those in lower social ranks as documented by archeologists. Here in Thailand, jewellery making and gemstone sourcing go back centuries. Gold travelled through Thailand some 2,000 years ago through Hindu settlers from India’s eastern and southern regions. About seven centuries ago, silver tooling emerged as a prominent craft. Today, Hill Tribe Silver is legendary worldwide for beautiful tribal and nature motifs. Chiang Mai is also famous for its distinctive silver jewellery.

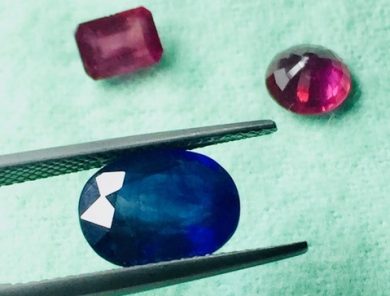

The tradition of gold and gem-based jewellery reached a peak in circles of power during the Ayutthaya era. Historically, rubies and sapphires were in abundant supply through the country. In its heyday, Thailand’s most coveted gems were the deep-red rubies mined in the Chanthaburi region since the 15th Century and blue sapphires from around Kanchanaburi. Now the local mines are largely depleted, yet the Thai industry evolved and gave rise today to a dynamic cutting and polishing epicentre that turns rough stones into glittering gems using the most advanced methods possible – some above board and others not so much. More than $650 million worth of gemstones are exported from Thailand annually, about half of that sapphire according to the Gem and Jewellery Institute of Thailand.

Today, Thailand is one of the world’s most prominent modern centres for gems and jewellery serving as a major hub of production, gem treatment and trading. Raw stones are imported to Thailand from around the world for cutting and treatment, much of it still happening in Chanthaburi, a town 150 southeast of Bangkok. Nearby many of the world’s rubies have been mined from Myanmar’s Mogok mine dubbed “Valley of Rubies” and known for the world’s finest “pigeon’s blood” coloured rubies, the majority of these stones make their way into Thailand for cutting, treatment and polishing. Other gemstones coming into Thailand today come from much, much further away: Rubies from Sri Lanka, Mozambique and Madagascar, sapphires from Australia, India, Tanzania and Montana, USA, jade from China, New Zealand and Myanmar, opals from Australia, and on and on.

Twice a year, each February and September, the global gem industry descends upon Bangkok’s massive Impact Challenger Hall at the Bangkok Gems and Jewellery Fair (BGJF). This event is ranked among the world’s most important and widely attended events of the industry. It’s here that all the key players in the global gems and jewellery business come to source, trade and network. It’s also an incredibly eye-opening and overwhelming experience for any novice jeweller. Row after row of vendors showcasing cases of loose cut precious and semi-precious stones – sapphire, ruby, aquamarine, tourmaline, spinel, garnet, peridot and more. Walking these aisles is a dizzying experience, especially when one considers the various ways sub-standard real stones are treated to yield a higher retail value. Layer onto this, the abundance of lab-grown stones that have gained more and more acceptance in mainstream markets. The next BGJF event will be held September 10-14, 2019 with the last two days open to public attendance. For anyone curious about the jewellery industry, it’s a must-see exhibition.

So, years after having my eyes opened by the boy king and long after professional stints working with luxury brands like Yves Saint Laurent and Shiseido, I decided it was serendipity to land in Bangkok and have the opportunity to reignite my interest in gemmology here in “The gemstone capital of the world”. And, thus began my brief tenure as an “apprentice” gemologist and jewellery designer as a student of the Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences (AIGS) located in Silom. Founded in 1978, AIGS was the first international gemological education centre in SE Asia. Today students come from all of the world to attend courses. In 2018, I joined their ranks for a series of short courses. Gem treatment and identification. Ruby and sapphire grading and pricing. Countertop sketching and design. For weeks, I trekked through Bangkok’s notoriously unpredictable, snarling traffic, crowded sidewalks and rainy season road flooding tormenting those within earshot with my poor Thai, “Wannee rottit maak maak,” “Ow gawfee mai wan” and “AC thangan yangrai”.

My classmates varied widely in age, background and experience. There was the dapper, 20 something Iranian jeweller in town for courses to sharpen his skills before returning to a family business; the hip Australian certified gemologist already with her own private clientele looking to polish skills and make new sourcing contacts, the Japanese Mom of two in Bangkok from London with a background in high-end jewellery sales and design aspirations. The scruffy American jeweller with a West Coast boutique keen on learning how to spot great finds and bargain well at the Chantaburi and Mogok markets. Then there was me. Communications professional in the midst of a long career sabbatical. Mother of 3 (still shorter than me) humans and 2 canines. Soccer Mom and yoga enthusiast. Part-time writer, passionate clean air advocate. And a curious, gemologist in training, perhaps? I didn’t fit the typical AIGS mould.

So, you might wonder, what on earth is a gemologist? Simply put, it is a specialist in gems. It’s the science of natural and artificial gemstones and gemstone materials. Typically, it takes years of academic study to become a trained and qualified gemologist. These experts spend most of their time identifying, grading and appraising gemstones. They’re also trained to conduct a series of scientific tests to confirm the identity, chemical composition and various other technical details of a specific gem. Many spend hours in labs analysing and grading gemstones of all types, while others work with auction houses to appraise gems, with jewellery designers to source materials and advise on designs, as buyers or sales people in retail.

For the average consumer, we think of gemstones in terms of an emotional response. Do we love the way it looks, the way it makes us feel? And diamonds are by far the most understood. Thanks to being well-anchored with the global engagement and wedding industry, diamonds are synonymous with the 4 C’s guidelines. But what of coloured gemstones? How are they rated and classified? And what is done to stones to make them look better and sell at higher price points? Quickly, I realised there is more to this story than one could imagine. Here’s what I learned about coloured gemstones and jewellery shopping.

A gemmology crash course:

Gemstones – know the 6 categories: Gemstones can be classified in one of six categories, understanding the technical differences will help when shopping the market.

Natural gem: They are made entirely by nature. The only human-altering to natural gems is through ordinary cutting and polishing. Much of what we see in the gem market place features stones augmented and treated with manmade techniques that go beyond skilled cutting and polishing, to improve colour and clarity. Natural gems are minerals with a special chemical composition and crystal structure that repeats itself. This unique combination of atoms has to be a perfect recipe to grow a gemstone.

Treated gems: Any natural gemstones that have been altered by people beyond ordinary cutting and polishing. This includes heat-treated, oiled and stabilised methods used on stones like ruby, sapphire, emerald, turquoise. Synthetic gems: This is a gem that has the same composition, structure, properties and appearance as a natural gem, except synthetic gems are lab-grown.

Manmade gems: The same as synthetic gems, but they have no natural counterpart. They are entirely lab-created. Assembled gems: Gemstones produced by assembling two or more pieces together. The pieces can be natural or not. They are referred to as “doublet” or “triplets”. For example, there is usually a natural stone on top and a synthetic base stone.

Imitation gems: A gem material, either natural or otherwise, that has the same appearance as the gem it imitates. Classic examples are cubic zirconia, famous as imitation diamond or red spinel, famous as imitation ruby.

Stone enhancement: They do what to make the stone look better?

Heat treatment: Virtually every coloured gemstone on the market has been heat treated, a technique rarely disclosed to the consumer. Proper heat treatment can turn a useless rough stone into one that is commercially viable and gorgeous. We can see a stone has been heat treated through clues detected under a microscope like crystals, “fingerprints” and blue spots.

Dyes and Oils: Stone cracks are filled to improve the stones clarity and/or colour. Upon microscopic examination, colour concentrations revealed in the cracks will give it away. Dyes and oils can also be prone to “sweat” or drip from cracks.

Lead glass filling: This technique is used to dramatically improve very poor-quality stones that have many cracks and cavities. Evidence of this treatment can be detected easily with a jeweller’s loupe revealing gas bubbles along fractures. The process itself can cause further stone fracturing. This enhancement practice is considered taboo; it makes the stone unstable.

Bleaching: Porous gems like jade, pearl and tiger’s eye quartz are often bleached to with acid to lighten and improve colour. It tends to make the stones more brittle and even more porous.

Rating stones: Hardness, colour saturation and clarity

Stones are rated for durability and resistance to scratching with the Mohs Scale of Hardness a one to ten ranking of minerals in order of their hardness. Diamond, ruby and sapphire ranking hardest, while emerald and jade fall in the middle making them among the most brittle, scratch-prone stones. The beauty of a stone is rated by saturation, how vivid

and rich is the hue, and tone, which evaluates the lightness or darkness of the

colour. In the case of coloured gemstones, we view stone clarity

as an evaluation of external surface blemishes such as stone scratches and

pits, and internal inclusions that can be seen by the eye, loupe or microscope.

These can be a fingerprint, growth pattern of the mineral or fracture. The more

easily visible the lower the grade. No two gems have the exact same set of

inclusions. The chances for truly exclusion-free gemstones are extremely rare.

Tools of the trade:

The dark field loupe and tweezers are the essential handheld instruments. The loupe lights a stone from the sides providing 10x magnification. It’s great for a quick look to reveal stone fractures and clarity-enhancements such as lead glass filling. For a 100% accurate gemstone identification and assessment on treatment history, a lab report from a certified lab such as AIGS or GIA using a microscope would be necessary.

Go off the beaten path, try unique and often more affordable stones:

There is a whole world of natural semi-precious gemstones that look very much like their higher priced cousins. But the bottom line is when considering gemstone jewellery, go with what you love. Find pieces that can be “everyday wearable” and often looking at a less travelled path will yield more affordable options. Consider tourmaline, citrine and peridot for their

vibrant hues in yellow, green and orange. Despite its low hardness and tendency

to chip, moonstone in the right protective setting such as cabochon makes a

stunning choice. Tsvarorite is a type of green garnet that evokes the look of

emerald, without the high price point or brittleness. Or opt for natural red

spinel or natural garnet in lovely vibrant hues of red instead of ruby.