Lebanon’s Bekaa valley

Our goal was the Bekaa Valley, on the other side of the mountains, a world away from Beirut’s skyscrapers, beach clubs and liberties. Just beyond the ski resort town of Mzaar, we passed the first of many military checkpoints we would encounter. The soldier was cradling a machine gun and looked shocked to see us.“Too-

Pot is illegal in Lebanon, though you’d never guess that driving around the Bekaa Valley. Extensive marijuana plantations grew right beside the road. I’ve seen estimates that 10,000 acres of pot

“Ahhhh! The legendary Lebanese Blonde!” “What are you talking about?” Kiva asked. “Nothing. Just be quiet and smile!” I shouted. I had hurried Nori and the boys out of the car for a cheeky family photo in the marijuana fields. Nobody was around, but it wouldn’t be wise to linger. Posters of Al Sadr, fallen intifada soldiers and Hezbollah slogans (always accompanied with images of raised rifles) peppered the roadway. There were army checkpoints everywhere, most of them unmanned, but ready for the next disturbance.

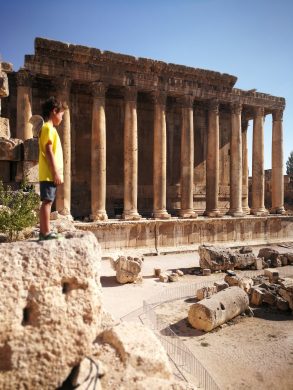

Today, on ‘Google’s most dangerous shortcuts” we’ll take you through dirt-poor Hezbollah villages, pot farms, refugee camps and armed checkpoints, all because Google Maps thinks this is the fastest way to Baalbek,” I said in my TV announcer voice. The modern (and by that, I mean recent) town of Baalbek barely hinted at the architectural and archaeological wonder hidden within its warren of constricted, convoluted streets. Even the signage seemed designed to mislead and infuriate; we kept looping through the same area. When we finally chanced upon the ruins, we couldn’t find a place to park. Heliopolis, certainly the largest and arguably the grandest Roman temple complex in the world had no parking lot.

Clearly, this was not going to be like visiting the Acropolis. Nori and I paid L15,000 (about US$10) each to enter the ruins. The boys got in for free. After declining the services of a kindly old guide, we ambled down a short path to the base of the propylaea – a monumental entrance staircase and gate with a portico whose long-collapsed roof was supported by massive columns. Once beyond the portico, we entered a hexagonal forecourt that led to the main courtyard – an expansive, arcaded square that was littered with the gear-like drums of tumbled columns. Beyond, reached by another stone staircase was the Temple of Jupiter.

Only nine columns and a section of their connecting architrave had been reconstructed, yet their size and grace left no doubt as to the awesome grandeur of the completed edifice. The Corinthian capitals that crowned the columns were twice as tall as Logan. The temple itself sat atop cyclopean stones of such prodigious size (three of them, the so-called Trilithon, weighed 800 tons each) – engineers still aren’t certain how they were moved into place. Though slightly smaller than the Temple of Jupiter, the adjacent and better-preserved Temple of Bacchus was nonetheless colossal.

In design, it resembled Athen’s Parthenon, but its scale was superior. I gaped at the detailed carvings on the entablature and the giant stone lions’ faces from whose mouths rainwater once gushed off the roof. The interior of the temple was just as impressive, its supporting columns bridged by decorative arches and pediments that once sheltered religious statues. Best of all, the boys were allowed to explore, climb and leap between the fractured stones. Or at least, no one stopped us. It was the most epic playground ever. They scaled the walls, scurried through tiny gaps in the rubble and did 360s off everything. If Heliopolis’ ruins had been thronged with tourists, the boys’ screams and laughter would have annoyed everyone. But there were so few visitors that I could just let them play.

Wine was being made in what is today Lebanon over 4,000 years ago, a fact impressive to everyone except the Georgians. It is no coincidence that Bacchus was worshipped here. Today, there are over fifty wineries in Lebanon, most located in the Bekaa Valley. Old Kingdom Egyptians loved wine from Byblos and Sidon. Even the Bible lauded Lebanese grapes and vino: Hosea 14:7 “They shall return and dwell beneath my shadow; they shall flourish like the grain; they shall blossom like the vine; their fame shall be like the wine of Lebanon.”Most fine wine is made in peaceful, bucolic areas with rolling hills, refulgent rivers, curving roads, vineyard views and stately trees. The Bekaa Valley, in our experience, had little of this classic wine country ‘romance.’ All of the tasting rooms we visited were located in dusty towns strung along the busy Chtoura-Nabatiyeh Highway. Domaine des Tourelles’ next door neighbours were a gun shop and a McDonalds. Chateau Heritage was secreted up a side street on the industrial fringe of Qob Elias. Coteaux du Liban was in a grubby, half-built area east of Zahle.

That said, the ‘wild frontier’ nature of the experience made wine-tasting in the Bekaa Valley unforgettable. What other wine region carries a US State Department travel advisory against visiting it? Nobody worries about getting kidnapped in Napa or bombed in Burgundy! For our part, we never felt the least bit unsafe. But knowledge of the Bekaa’s turbulent history and current tensions created a frisson that you could almost taste in the glass. The wines were exciting. Moreover, the friendliness and magnanimity of the winemakers and their staff

We tasted through their entire collection over a two hour period and, after I bought three bottles, they gifted us another. Then the winemaker, Dr Touma, stopped in and his first question was “Are they taking care of you?” We replied enthusiastically in the affirmative and he still gave us another bottle gratis.