Cedars and Canyons

At the base of the mountains, near a shabby army camp, three young boys loped alongside our car until we had mercy and bought them a couple of watermelons. We passed no other cars during the long, hot drive back out of the Bekaa Valley and over the Lebanon Mountains. Halfway up, I left the car with the hazard lights flashing while Logan and I crossed the road and had a glorious, father-and-son pee looking East over the valley toward Syria. As we climbed, I heard thunder and saw a grey plume rising from a distant brown slope – heavy artillery practice.

An ageing lorry sat atop the pass. Its bonnet was up, the engine cooling. The driver was slumped on the steering wheel napping, until the boys rushed out of the car and started a shouty rock-throwing contest. The saddle was in the middle of a long, scalloped arc of desolate, tan mountains. When rain fell, or snow melted, all the water from an enormous catchment area flowed, mingled, gained force and gouged the parched ground. Through a haze of heat and dust, we could just discern the Kadisha Valley – Lebanon’s “Grand Canyon” – to the West.

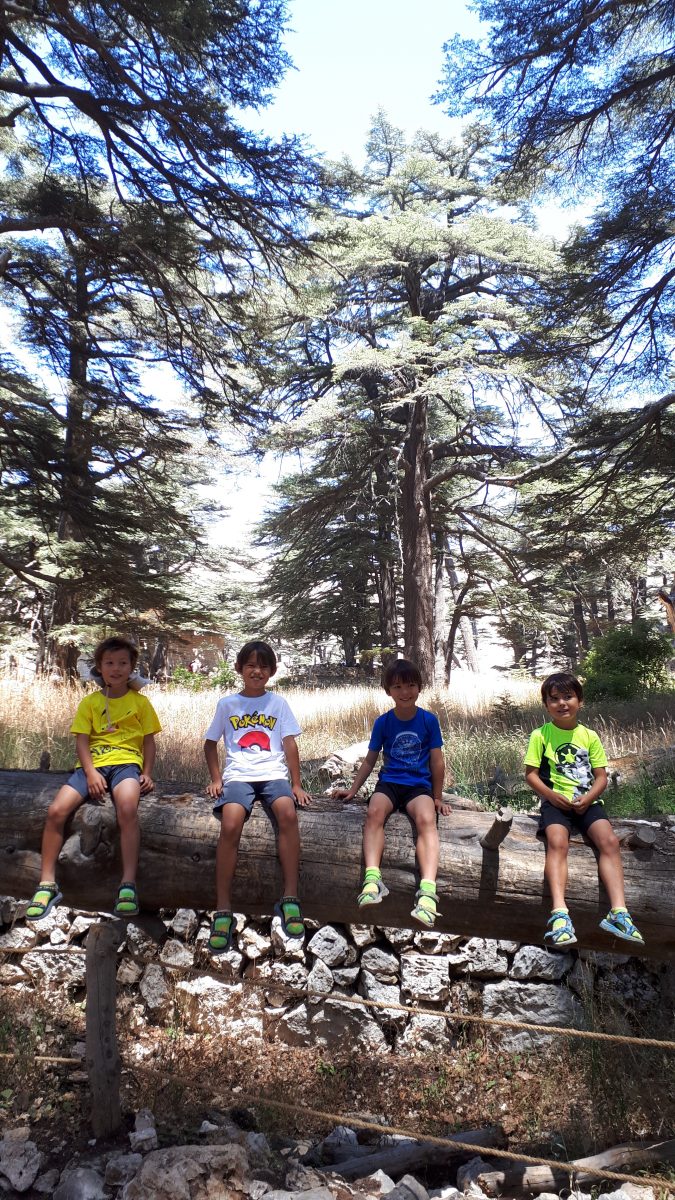

In stark contrast to the monochrome brown mountains surrounding us, a broccoli-like burst of green spread below us. The Cedars of Lebanon! These slow-growing, uniquely branching trees used to dominate Lebanon’s highlands. But after thousands of years of logging, disease, infestations and climate change, cedrus libani survives today only in isolated groves. Protecting this tree, the symbol of Lebanon’s long history, strength and resilience, is one thing that an otherwise deeply divided country can agree on.

To reach the Cedars of God reserve, we had to pass through a gauntlet of souvenir stalls selling mostly wood carvings: swords, bendy snakes and the best-seller, cedar-shaped family trees with your names etched with a wood-burning tool into the branches. Surely, these weren’t made of cedar wood? Even if they weren’t, it was beyond bizarre, like selling imitation-ivory carvings outside an elephant sanctuary. The boys were starving, so we ordered a couple of pizzas and sat on a rooftop terrace overlooking the grove.

As we started down the trail that looped through the grove, I came to an abrupt stop. Improbably, I recognised the trees in front of me. But how? With a jolt, I remembered: the Bible given to me by First Lutheran Church for my Confirmation in 1982 had several pages of colour photographs. Later, I confirmed that the inside cover photo of my Bible was of this very spot – a cluster of four cedars with a hazy ridge of tan mountains behind it. How much my life had changed in thirty six years! But this was but a moment in the Methuselah-like lives of the cedars.

The righteous shall flourish like the palm tree: he shall grow like a cedar in Lebanon. – Psalm 92:12.

A few miles down the road, I spied a promontory uglified by the concrete cube of an unfinished building. It took some time to locate a road that led there. While the boys watched another Pokemon episode in the car, Nori and I walked out to the point. The concrete pillars were wrapped in barbed wire; had this been an artillery site? Just below us, the land collapsed into a tremendous, concertinaed, grey and green chasm. This was the Kadisha Valley, with the pretty town of Bcharre spilling right down to the edge of the canyon.

I don’t read self-help books, despise motivational quotes and I am skeptical of anyone claiming an elevated spirituality. I read The Prophet purely because Khalil Gibrain was the most famous Lebanese author I could find. The Lebanon section at Daunt Books in London comprised but a few, overwhelmingly political, volumes in the Middle East section downstairs.

Surprisingly, I adored The Prophet. A beloved seer is leaving his city; the citizens have but a few hours to seek his counsel before he boards a ship bound for the horizon. With delight, I read and reread the tiny chapters, each built around a single question from the crowd and the prophet’s lyrical, universal response. Was he Jesus, Mohammed or John Smith? None of them and all of them. The message was about love.

Gibrain was born in Bcharre. In the 1920s he lived and wrote The Prophet in New York. Upon his death, his remains were returned to Bcharre and the old monastery he had bought and renovated was eventually turned into the Gibrain Museum.

I rarely fly my drone over cities. I’m terrified by the prospect of a rotor snapping and the 1kg device braining someone as it plunges. Drones aren’t like airplanes. As I had seen in Koh Kradan, Thailand, the loss of even one rotor sends the drone into a dive that the software can’t correct for.

However, I decided to make an exception. I pulled off the road just above Bcharre and used our car to conceal the launch. So steep was the hillside that just by flying straight, the drone was soon hundreds of metres above the city, looking down on the twin spires and central dome of the Mar Saba Cathedral, a stone’s throw from the cliffs of the Kadisha Gorge.

I would have loved to do a hike into the gorge, but it had already been a long day of driving and we were all looking forward to a shower and a decent night of sleep back in Beirut. While my family slept, I followed the Bcharre-Tannourine Road around to the southern side of the gorge and spent an hour trying to contain my amazement as the road followed the squiggly edge of the abyssal gorge.