An author in lockdown

On the face of it, a global pandemic should be perfect for a writer. It requires society to keep itself at arms length, maintain a respectable social distance, visit nowhere, apart perhaps from the pharmacist or the greengrocer. It should be a boon for a writer. There is a perceived wisdom; all a writer needs is an idea, a pen and lashings of solitude – right? Well, only partly right. Let me explain.

I was last in my beloved Thailand, a year ago. It was there, as I prepared for a brief visit to Europe, an expat friend questioned my judgement.

‘Flying back to London, Frank? Are you sure? This Covid thing looks worse there than here. I’d stay put if I were you.’

This was March 2020, and the early days of the plague. Thailand had been one of the first countries, after China, to report cases and some were holding their breath, waiting for the disease to grip. In England, people were only just beginning to look over their shoulders; still telling themselves it was someone else’s problem.

‘I have to get back; I have some banking to sort out.’ I replied indifferently.

All true; I was in the middle of buying an apartment and needed to sort out the finance. Something also told me I might be better off in England though; for a while anyway. Europe would handle the crisis better and once the dust had settled, I’d be back. A few short months should do it. How wrong I was; particularly because the apartment in question was in Chiang Mai…

Back in the watery sunshine of a Sussex Spring, I quickly sorted out my funding and sat down to scope out the new novel. It was to be set in nineteenth century Siam – a political and espionage thriller, with a cast of vibrant English and Siamese characters. I was excited. Then, as my thoughts started to come together, the Thai travel restrictions were announced. I convinced myself that by August all would be well, so with plot ideas rumbling around in my head, and an assortment of scribblings, I settled down to write the first chapters in England.

One of the challenges of writing a historical novel, set in a faraway country, is to deliver authenticity. I pride myself on realism, and I relish the chance to research the terrain. To be honest, the exploration is usually the best part of creating a story – that, and the sense of total immersion. When writing my earlier novels, I’d spent extended periods in some of the remoter parts of Thai border country, meeting folk who treated ‘farang’s’ as amusing novelties. I trudged up mountain trails, through dense, bird filled forests, to descend to sparkling river valleys. I always wanted a chance to experience what my characters might have felt. But now, here I was, marooned in a flat just outside Brighton, and worse, I was stuck in a cramped loft space with a view over Tesco’s carpark, with strict orders to stay put.

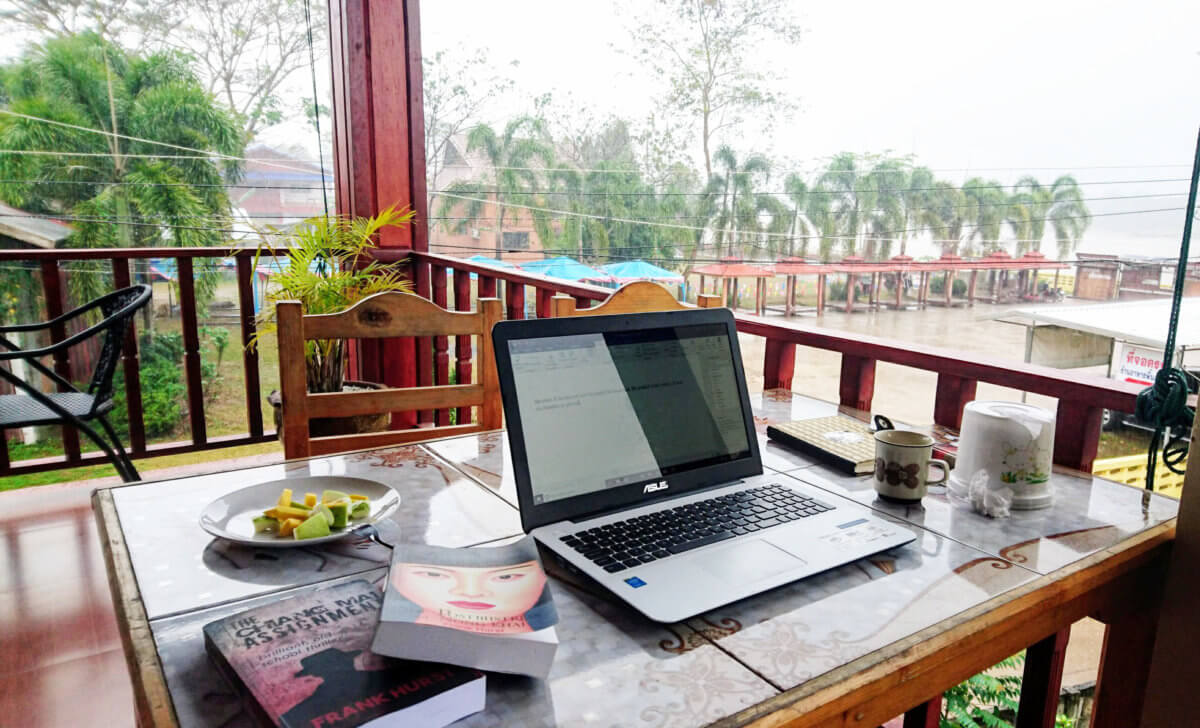

I reverted to the internet for company, but informative as it was, the feel, the atmosphere, the essence of the place I aspired to write about was somehow missing. I tried to imagine myself back; I yearned for the solitary veranda in Baan Nam Suaay, with its view over emerald green rice fields, the smell of lemongrass, the shack I’d rented above the western reaches of the Mekong River, the spice market in Nong Khai; I could go on. After a month of wrestling with the wrong words, I gave up on ancient Siam – nothing worked. To write about Thailand, I needed to be there. The internet and the guide books were no substitute for serendipity and boots on the ground.

Instead, I turned my hand to writing a thriller, set in Victorian London. Suddenly, Brighton’s Covid lockdown seemed to be an advantage. It was easier to imagine the cold cobblestones of foggy London streets than the grand majesty of Wat Arun at dawn. Simpler in my mind’s eye to visualise a shrouded hansom cab against a lamp lit Thames embankment than a rickshaw bumping down a track by a bustling Chao Phraya river. But there were still distractions. I developed a new and morbid fascination for the Coronavirus statistics of death – the growing pandemic was providing plenty of those. The figures now read like a lopsided and gruesome tally from a Somme battlefield. The United Kingdom 110,000 – The Kingdom of Thailand 79. Goodness!

But, by this time, my forced isolation had started to focus my mind. Gone were the invented diversions; the unnecessary shopping trips and car rides to country pubs. I had no visitors, and when I turned my phone off, I had no calls. I became absorbed in the London of Jack the Ripper.

But then, just as my new project was beginning to show some promise, officialdom struck, and the whole equilibrium of my imprisoned existence would take a nasty jolt. I thought I had become immune to the many and sometimes charming quirks of Thai bureaucracy, but this experience left me scratching my head. The saga began shortly before I’d left Thailand a few months earlier. I had a tax bill to pay; it was connected to the Chiang Mai apartment that I was buying. The Land Office, quite rightly, wanted their money. So, I took myself to my local bank, and from my savings account, I withdrew a cashier’s cheque to cover the new demand.

At this point, almost before the ink had dried, Thailand’s Covid defences started to manifest themselves. Police barriers went up on the beach road, and there was talk of quarantine. Abruptly, the Land Office closed its doors to all comers, including me. Three weeks passed before they opened for business once more, but by that time I’d returned to England and had already started to despise the view of my Sussex supermarket. On presentation, the Land Office advised that the cashier’s cheque was no longer valid – it was past its sell by date – literally. Another would be required. No worries, I thought; irritating perhaps, but not insoluble. I contacted my branch by phone from England, a kind lady banker took on board my request and without hesitation she issued a brand new cheque on my behalf. The Land Office duly accepted it, and my tax debt was paid – everyone was happy. There was just one thing required; to tie up the loose ends. I had to cancel the original cheque, and get the sum repaid into my account. I called them once more. But this time, the transaction would not prove to be so easy.

I would need a power of attorney, the bank said. It would have to be prepared in Thai and English and signed by me (in blue ink). Then, in the following order, a notary lawyer in UK, The British Foreign Office, The Royal Thai Embassy in London and finally, once returned to Thailand, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Bangkok would have to add its moniker and stamp to it. The power of attorney would have to be accompanied by a signed copy of my passport photograph page, a signed copy of the relevant visa page, a signed copy of my bank book, and a signed copy of my appointed agent’s Thai ID card. The last signature, from the bank itself, would finally enable them to return my money. With a sigh of surrender, and realising that there was no point in remonstrating, I set myself up, square jawed, to tackle the task. Unfortunately, the Victorian novel stalled as a result, as I became obsessed with this new challenge.

Eventually the great day arrived; I had obtained all the required signatures. I shipped the papers back. But when presented with the wad of signed and stamped documents, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs decided that in order to process the application, I would need a second power of attorney; this to authorise my appointed agent to apply to them to legalise the first power of attorney…

I’ve tried to remain calm… but one question keeps repeating itself; it was vaguely teasing at first, gently reproachful perhaps, but with each asking, it has become ever more strident, ever more accusatory.

‘Frank! Why the hell did you abscond from Thailand in the first place? Now look what’s happened. Your tour de force Siamese novel has been put on ice, your half baked Victorian thriller is less than three chapters old, the destiny of your money is in the hands of overseas officialdom, the only people you see are hooded shapes pushing shopping trolleys, and despite your appalling isolation, you are closer to contracting Covid than ever before. What were you thinking about, man?’

There is absolutely no doubt. The glitches of local officialdom may have been mind-bendingly frustrating. But more than ever, I am missing Thailand horribly, painfully. The smell of lemongrass, the Indochine spice market in Nong Khai, the sound of bamboo on a windy day, the taste of Khaw Khaw Hmu, the borrowed shed on the banks of the brown Mekong, my battered motorbike, and even the screech of the damn cockerel that used to wake me most mornings to mark the sun rise of another Isaan day. A year has passed since my banishment, and it looks like it will be many more months before this terrible scourge is conquered. Life must go on – I will survive.

I just wish I was surviving in Buriram, not Brighton.

Frank Hurst is an English author who writes crime and adventure novels about Thailand

Website: Frankhurst.com