Wellbeing and schools in a changing world

Some of us look back on our schooldays with misty eyes and a nostalgic sense of longing for lost youth. Others may remember a prison of relentless torment and stark, meaningless unhappiness. Many recall perhaps both, to varying degrees. Today as adults, we may have children of our own; but are they facing the same demons?

In some ways the answer is probably yes: it is not always easy being a child, especially as age reaches double digits, but saying ‘schools have changed’, or ‘schools haven’t changed’ does not really explain enough. Schools are not now – nor have they ever been – all the same. What we as parents are faced with today is a range of choices that can make a significant difference to our children’s lives both now and for the future. Working through those choices can be a frustrating affair, so Iet us examine a few of the current areas of focus in schools.

What are schools for?

On the surface, the easy answer is: schools are for learning, which

begins with ‘primary’, or ‘elementary’ education: reading, writing and using numbers. This should give children a foundation of skills, knowledge and understanding to be able to function effectively and independently in society. Then the learning moves on to ‘secondary’ education, where those basics are applied to more complex, specific areas such as science, literature, languages, mathematics and so forth. This should enable young people to enter the world of work, or their university of choice, with confidence.

This explanation is essentially correct – but it is also a long way from being the whole story. School is for a lot more: we must remember the truth that our children are not just pupils or students, they are also human beings who think, feel, like, dislike, play, suffer, worry, enjoy and live. As a teacher, I am aware that it is quite easy to perform teaching without acknowledging this truth, by simply standing at the front, drilling your charges about facts and figures, assigning tasks and administering punishments when someone is disobedient. That is the image many people have of teachers – and, in some (but not good enough) ways, it is an approach that works.

So what is modern day teaching like?

The best teaching and, therefore, learning in school is not just about book learning (though that remains a very important element) and obedience delivered wholesale by omniscient teacher leaders to omni-ignorant pupil followers. Education should never just be an exercise in information transfer, from teacher to student. This is a more valid point in the 21st century than ever before: if your smartwatch can access Google Search, why do we need to know anything anymore? Actually, there are plenty of good reasons for still knowing things, but knowledge these days is no longer power in the traditional context.

Today, knowledge is fuel for thinking.

Thinking is fascinating when you, well, think about it. Of course, we are all thinking most of the time – some conscious activity is happening in our brains – but the thinking that a good school teaches is a more structured process. It is fundamentally scientific method: observe, formulate ideas, gather information, analyse, identify what is true, and repeat. This applies equally across the whole range of classes and activities that take place in school.

A Robotics class experiments with alternative means of fulfilling a challenging brief; a Mathematics class explores the properties of three-dimensional shapes; a Physical Education class undergoes different training methods to discover which works best; a Mandarin Chinese class tests out alternative grammar structures until the correct ones start to make sense. Trained in this ability to be rational, children can become independent minded and think intelligently for themselves. This is possibly the most important goal of top-quality education: giving children the tools to create paradigms, not just to understand those that already exist.

What is ‘educating the whole child’?

As well as ‘thinking’, all good schools these days talk about ‘educating the whole child.’ At Wellington College, what we mean is taking seriously, as part of the fabric of education, everything and anything that children may have interest in, aptitude for, and motivation towards, and not simply using it as an add-on or a piece of sales-friendly decoration. We take it so seriously because we recognise that all learning is valuable and it all contributes to the creation of the person we become.

So our curriculum itself is broad and deep, embracing the widest range of subjects and disciplines, but further than that, we schedule further productive activities, in sport, music, creative and performing arts, coding and so forth as part of the regular school day. And the staff interact with the students in multiple ways – not just as class or subject teachers but also as pastoral guides, coaches, mentors and, sometimes, peers in learning. (My own experience of learning to ski at age 47 on a whole school ski trip, alongside 11 year olds of much greater ability and potential, is a story for another day!)

But even that is still not the whole story. One of the comments I hear most often from parents is ‘I can’t understand it – my child seems to love school. I hated school when I was young!’ Naturally, I am delighted to hear it, although to some extent I am sure the parent may have somehow forgotten all the good times. One of our aims as modern-day teachers is to create the conditions for children and young people thoroughly to enjoy, and make the most of, school. However, full-time enjoyment – twenty-four-hour-a-day, seven-day-a-week happiness – is just not feasible, either in or out of school. Life does not, and cannot, work that way.

What is ‘Wellbeing’?

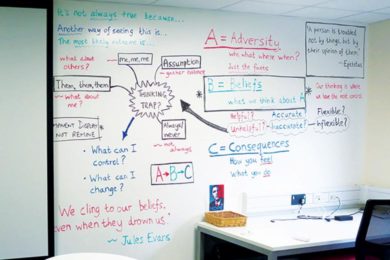

And so to Wellbeing, the final big piece of the puzzle. To be exact, Wellbeing does not teach us how to be happy, but it does teach us how to be ready to be happy: how to be resilient, emotionally strong, open minded, thoughtful, mindful and aware. It teaches us to take responsibility for our actions and our feelings, to think critically and to care about others as well as ourselves. It is not a topic that we grade (life does that for us) but it is one we take very seriously at Wellington College.

Wellbeing as part of a school curriculum was pioneered more than a decade ago at Wellington College in the UK. In 2006, the school’s then Master, the legendary Dr Anthony Seldon, and Ian Morris, a teacher of the traditional PSHE course (Personal, Social and Health Education), teamed up with Dr Nick Baylis, then a lecturer at Cambridge University, to develop a unique course designed to provide young people with a set of emotional and intellectual skills which would enable them to approach, confront and move past the challenges and difficulties that life inevitably places in all our paths.

A decade may not seem to be a long time in the history of education, but in that time Wellbeing has gone from being viewed as a fringe or gimmicky notion to being a subject that is increasingly popular in schools, particularly British and British-style schools, around the world.

In fact, many of the roots of Wellbeing as an area for study actually stretch back more than twenty three centuries, to the work of Aristotle and, specifically, his view that how well a person reaches her potential is the measure of how successful, or happy, that person ultimately is. For Aristotle, it is the exercise of Virtue (generosity, courage, friendship, even-temperedness, and so on) that leads to this goal.

Learning Wellbeing involves finding out about ourselves – our own personal strengths and weaknesses, aptitudes, abilities and so forth. In his recent book, ‘Behave: the Biology of Humans at our Best and Worst’ (2017), American neuro endocrinologist and author Robert Sapolsky notes that human biology is ‘about propensities, potentials, vulnerabilities, predispositions, proclivities, interactions, modulations, contingencies, if/then clauses, context dependencies, exacerbation or diminution of preexisting tendencies’. So it is with Wellbeing: we recognise and appreciate that people are individuals, not cookie cutter products of either environment or genetic inheritance.

And since anything can make a positive or negative difference to someone’s development, we believe the best way to support children during their formal education is by helping them to be aware, proactive, thoughtful and strong at their core, as people who understand what is happening, rather than simply reacting to events and occurrences.

A note on technology

Some years ago, technology was a serious sales point: one-to-one laptop schools; Apple environments, iPads in every classroom, and so forth. Some schools tried to go paperless and a lot of experimenting occurred. Then, to some extent, the brakes were applied (or at least seat belts were fastened) as the weaknesses, as well as the dangers, of Connected Education became clearer.

Use of digital technologies is now second nature to children and (many) adults and we are no longer so excited by the shininess of our new toys. Today, the key issues are security (we need sophisticated filtering systems to protect children); responsible use – a lot of work goes into this; a healthy balance between digital and analogue work; smooth communication; and up-to-date access to enormously exciting opportunities for collaborative and creative study and research. As educators, we are constantly committed to finding the Goldilocks zone – not too much and not too little – for technology in the classroom.

So when it comes to Wellbeing, or Technology, or anything else in fact, there is no ‘one size fits all’ educational model that works. When we are not only asking ‘what is the coefficient of friction?’, or ‘what does a jellyfish eat?’ but also ‘who am I?’ and ‘how can I make other peoples’ lives better?’, every answer, for every individual, will be different. At the best schools, what you get is a truly individualised, progressive education, allowing for the fullest and most powerful exploration of the answers to these and many, many more questions.

Christopher Nicholls is the Founding Master of Wellington College International School Bangkok. He has worked in some of the world’s top British schools, in the UK, Europe, Singapore and Tokyo. Wellington College is one of the UK’s most well-respected schools, with an enviable reputation as a genuine leader and innovator in the field of educational philosophy and practice in the UK and, increasingly, across the world.